Unpaid Labour: A Cornerstone Issue

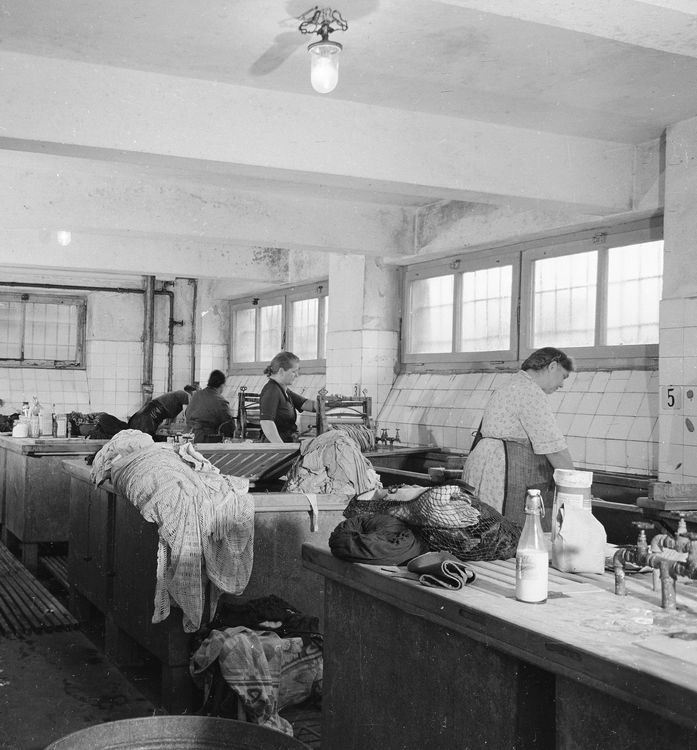

Women have disproportionately performed unpaid labour, which includes domestic work such as cleaning and cooking, caregiving (childcare, eldercare), subsistence farming, and community-related work. This has limited their availability, career choices, and earning potential, leading to economic vulnerability, reduced workforce participation, and barriers to career advancement and political organizing. Today, the post-1968 women’s movements, such as the Italian “Wages for Housework” campaign, are often credited with bringing attention to the issue of unpaid labour. However, research on women labour activists in Central and Eastern Europe and Turkey and internationally suggests that working-class women had been addressing this issue long before the 1960s. Activists from the interwar period onward developed a vocabulary to describe women’s “double burden” of paid work and domestic labour, as well as the additional strain of social and political activism, which they referred to as the “triple workload”.

Activists approaching unpaid labour

From the late nineteenth century onward, women labour activists consistently identified unpaid labour as a key factor in women’s economic and social subordination. They recognized that the structures of paid work were built on the assumption that workers were free from domestic responsibilities, an assumption that did not reflect the lived realities of most women. This structural inequality remained a major obstacle even as women gained greater access to paid employment. And while women labour activists have early on identified this tension as a central issue they needed to address, their approaches and solutions varied significantly.

Melon farmer and his family, 1920s (Source: Hungarian Agricultural Museum and Library, EF_12918)

One of the most significant challenges women labour activists have faced in Central and Eastern Europe – regions deeply marked by economic hardship – was persistent material scarcity. Economic instability and poverty shaped the ways how lower-class women envisioned progressive change. Many working-class women could not afford to view paid labour as a path to personal independence because their wages were often insufficient to sustain them without additional familial or communal support.

This economic reality led many women activists to advocate for policies that would support working mothers and families rather than prioritizing women’s individual economic opportunities. Many say proposals such as mothers’ allowances, which provided direct financial support to women for their unpaid care work, as viable strategies for improving women’s material conditions while acknowledging the adverse effects of the gendered division of labour. Some activists viewed these measures as complementary to efforts to socialize housework and childcare by expanding public services, while others saw them as an alternative to pushing women into the paid workforce. However, both approaches faced structural challenges including resistance from policymakers, economic constraints, and prevailing societal attitudes that reinforced traditional gender roles.

Protection vs. legal equality debate

Throughout the twentieth century, women’s labour activism was shaped not only by economic conditions but also by ideological competition. It played out at multiple levels: within labour movements that were overwhelmingly dominated by men, between different factions of the women’s movement, and on the global stage, where competing political ideologies sought to define the future of women’s work. In the early 1930s, social democratic, communist, and Catholic women’s organizations, for example, engaged in renewed debates over women’s right to work that were shaped not only by economic crises and the rise of authoritarian regimes but also by their political competition with each other as they sought to attract more women supporters.

From the nineteenth century onwards, many women labour activists, especially those with trade unionist backgrounds, responded to the exploitative labour conditions women faced by advocating for women-specific protective legislation. These activists viewed special protections for women, such as maternity leave, special working hours for women, and restrictions on women’s night work, as essential for safeguarding women’s health and economic stability while allowing time for women’s household chores and caregiving tasks. Other activists argued that such measures risked justifying discrimination against women in the workforce and could reinforce employers’ reluctance to hire them, ultimately perpetuating women’s inferior position in the world of paid labour. Instead, these activists advocated for full legal equality between women and men as the solution. Some paired this vision with concrete demands to improve the position of all workers, regardless of gender, while others believed such improvements would naturally follow once legal equality was achieved.

Women queueing during World War II in Prague (Source: Topfoto)

State socialist stances

In the state socialist countries in particular, women activists approached this issue from a partly new angle. They did not see a contradiction between special protections and gender equality but rather believed that these protections were necessary for achieving substantive equality. Since socialist ideology sought to eliminate exploitation, activists under state socialism assumed that the political and economic system itself would ensure that women’s protections did not become a justification for their exclusion from or discrimination in employment. They envisioned a future in which employer power was diminished or eliminated entirely, allowing women to enjoy both protective legislation and equal status in the workforce.

State socialist regimes often claimed to be progressive on women’s issues, using the expansion of women’s employment and childcare provisions as evidence of their commitment to gender equality. However, this rhetoric often masked the reality of ongoing gendered exploitation. While women were encouraged to work, they were still expected, to take a greater share in the burden of unpaid care and domestic labour, which at the time was described as women’s “double shift”. This contradiction was rarely addressed in official policies.

Women’s activism beyond the workplace

Women performing the overwhelming bulk of unpaid labour deeply impacted not only the goals but also the practice of women’s labour activism historically. It meant, for example, that their activism often took place beyond the traditional space of labour struggles: the workplace. Women engaged in activism that directly built on their roles as caregivers and household managers. This included managing strike kitchens and organizing community care for the children of striking workers, as well as advocating for environmental policies that would protect their families’ well-being. While women, especially in the earlier period, were excluded or at least heavily marginalized in political and civic life, they sometimes managed to take advantage of this peripheral position in their activism. Subverting their perceived roles as apolitical housewives, women activists engaged in risky underground political work. They smuggled prohibited literature across the border, like Polish socialists did in the Russian Empire, or distributed anti-government communist appeals in interwar Romania and post-World War II Austria.

Despite significant political and economic changes over the past century, the issue of unpaid labour has remained a central concern for women labour activists. While progress – however uneven – has been made in terms of education, workplace rights, and social protections, the fundamental tension between paid and unpaid work continues to shape women’s experiences in the labour market and as labour activists.

Women labour activists in both state socialist and capitalist contexts have sought to address these issues through different strategies. Some focused on securing protections and financial support for women’s unpaid labour, while others aimed to socialize care work or challenge traditional gender roles. However, no single approach has fully resolved the structural inequalities that gendered unpaid labour creates. Recognizing the historical continuity of these struggles is essential for understanding contemporary debates about gender, labour, and economic justice. Women’s unpaid labour has always been the bedrock of society, and as long as it remains undervalued and unequally distributed, it will continue to be a focal point of women’s labour activism.