Everyday Labour as Politics: The International Co-operative Women’s Guild

In the interwar years, activists in the co-operative movement started to politicize women’s household labour and organize across country borders. The International Co-operative Women’s Guild (ICWG), founded in the early 1920s, became a rare international platform where housewives, workers, and activists from different political systems debated how to improve conditions of household labour, access to education and better nutrition, and social rights. At a time of growing ideological polarization in the labour movement, the Guild still managed to draw together social democratic and communist women. From its beginnings, it sought to transform the position of women in co-operatives and to connect domestic work to broader economic and political concerns. Among the figures central to this project was Emmy Freundlich (1878–1948), an Austrian co-operator who served as the Guild’s first president and played a key role in building its networks in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe.

Portrait of Emmy Freundlich (Source: Austrian Parliament)

At the International Co-operative Alliance congress in Basel in 1921, Freundlich co-organized the first international meeting of co-operative women. The event laid the foundations for what became the International Co-operative Women’s Guild (ICWG), officially established in Ghent in 1924. Freundlich was elected president and remained in this role until her death in 1948, giving the organization continuity across a turbulent period marked by economic crisis, political polarization, and war.

From its beginnings, the ICWG was shaped by the idea that housewives and mothers were not only consumers but workers in their own right. At the Stockholm conference in 1927, Freundlich addressed the delegates by insisting that “the housewife’s work is still always regarded as an inferior economic service in the life of nations”. She urged that “all the many housewives who work in the cells, so to speak, of our economic organism – the homes – must be united and educated by our Guild”. This understanding of domestic work as part of the economy was unusual at the time and became a defining feature of the ICWG.

ICWG Conference in Stockholm, 1927 (Source: Hull History Centre, Hull, England)

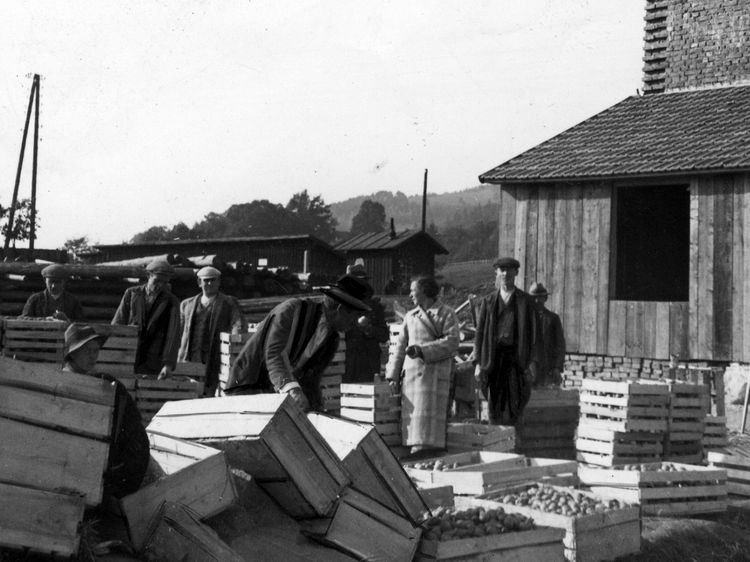

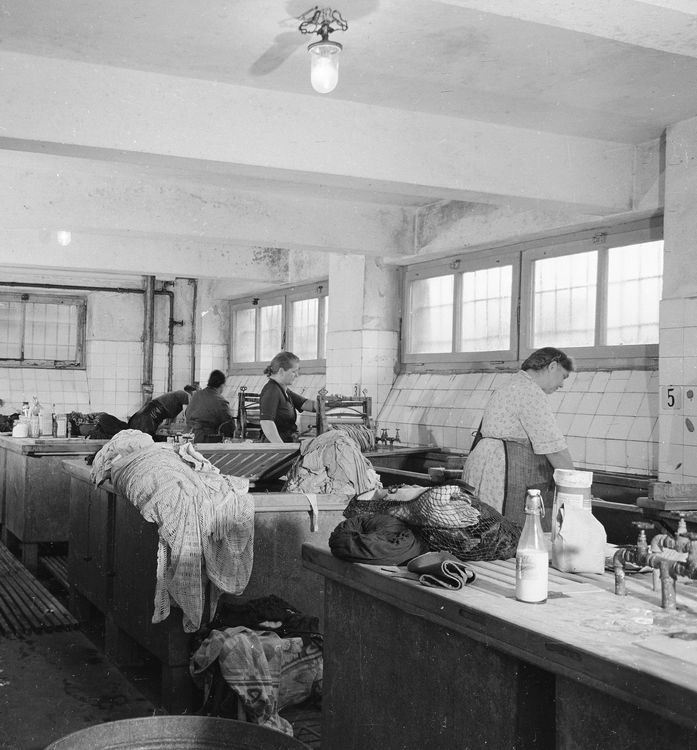

The Guild’s agenda linked everyday household labour to international politics. Its members discussed how to relieve the burdens of domestic work through labour-saving devices, co-operative services, and public provision. Laundry became one of its early case studies. In Stockholm in 1927, the ICWG presented The Family Wash, a comparative study of how clothes were washed across Europe. The report described washing as “the most burdensome” part of women’s work and recommended solutions ranging from electrified communal washhouses to co-operative laundries.

Through Freundlich’s leadership, the ICWG steadily expanded its membership in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Austria was among the founding members, and Czechoslovakia joined in 1927. The Soviet Union followed in 1929, the German organization in Czechoslovakia in 1930, and Bulgaria in 1931. Ukranian organization in Poland joined in 1933, and Poland in 1936. The Guild’s international debates went hand in hand with practical projects, and the activities in each country reflected the variety of contexts in which women’s co-operative activism developed. In Poland, guild members campaigned for mechanized washhouses, while in Bulgaria women organized courses in domestic economy for women in rural areas.

The international conference held in Vienna in 1930 highlighted the diversity of proposed solutions within the ICWG. A publication prepared for the meeting, Mothers of the Future, brought together different views on how to support mothers burdened by wage work and household duties. A Czechoslovak social democrat, Marie Nečásková, called for state allowances that would allow women to dedicate themselves to motherhood without financial dependence on their husbands. By contrast, the Soviet delegate Helen Butuzova argued for communal services – crèches, kitchens, laundries – combined with a broader socialist transformation. Freundlich presented a third contribution, stressing that women’s preferences and traditions mattered, and pointing to the potential of labour-saving devices. Rather than setting a single line, the ICWG under her presidency allowed such debates.

The Guild sought to insert the issue of household labour into wider international discussions. In the mid-1930s, Freundlich presented the ICWG’s “Housewives’ Programme” to the League of Nations and the International Labour Office, pressing for recognition of domestic work as a valuable economic service and linking it to questions of nutrition and health. Despite not achieving the official presence they strove for, Freundlich and other activists of the Guild continuously circulated memoranda that drew attention to how heavy domestic work could affect women’s health, including maternal mortality.

Poster for the festivities on the International Co-operative Day in Vienna, 1926 (Source: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, P-25020)

Freundlich’s presidency ensured that the ICWG became a space where women from very different national and ideological backgrounds could work together. Some Central and Eastern European guilds brought perspectives shaped by agrarian societies and economic hardship, while others, like the Czechoslovak ones, were more focused on the urban contexts and often emphasized reform through consumer co-operatives. The result was not a single programme but an ongoing negotiation of how everyday domestic life might be reorganized.

When Freundlich described the home as one of the “cells” of the economic organism, she was capturing the Guild’s guiding principle: that what happened in kitchens, washhouses, and nurseries mattered to the economy and to politics. By holding together debates across borders and ideologies, she helped make household labour an international issue in the interwar years.