A Tool for Building a Fairer World? Women’s Co-operatives

In the first half of the twentieth century, a lively and diverse co-operative movement emerged internationally, and women from Central and Eastern Europe played a prominent role in it. What was the relationship between women’s labour activism and co-operatives, and what were the key goals that shaped the efforts of women activists within this movement?

Understanding co-operatives

The co-operative movement relies on grassroots ownership and mutual assistance. According to the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA), a co-operative is a people-centred enterprise owned and run by its members, working together to fulfil their common economic, social, or cultural needs. Historically, the co-operative movement has been diverse, encompassing various models such as consumer, credit, producer, and worker co-operatives, to name a few. Many co-operatives were mixed-gender and actively enrolled women members, offering them a unique platform for activism and self-determination. These grassroots organizations connected with each other, building larger associations, sometimes called “guilds”. Although the women’s co-operative movement in Central and Eastern Europe has been shaped most prominently by communist and social democratic ideals, co-operatives inspired by other political and religious ideas, from anarchism to Catholicism and conservatism, also existed.

“Unite and educate half mankind”: Co-operatives and women’s labour activism

From early on, the co-operative movement has boasted a comparatively high proportion of women participants, including women activists in leading positions – even during the period when trade unions, for example, were still reluctant to include women in their ranks. Women’s involvement in the movement sometimes stemmed from their responsibilities within the household. Working-class women traditionally played the role of family “scarcity manager”, ensuring food was on the table and basic supplies such as soap and clothing were available even when times got rough. Because they were making family finances stretch, women became almost natural participants in consumer co-operatives that aimed to make better-quality products available at more affordable prices by leveraging economies of scale.

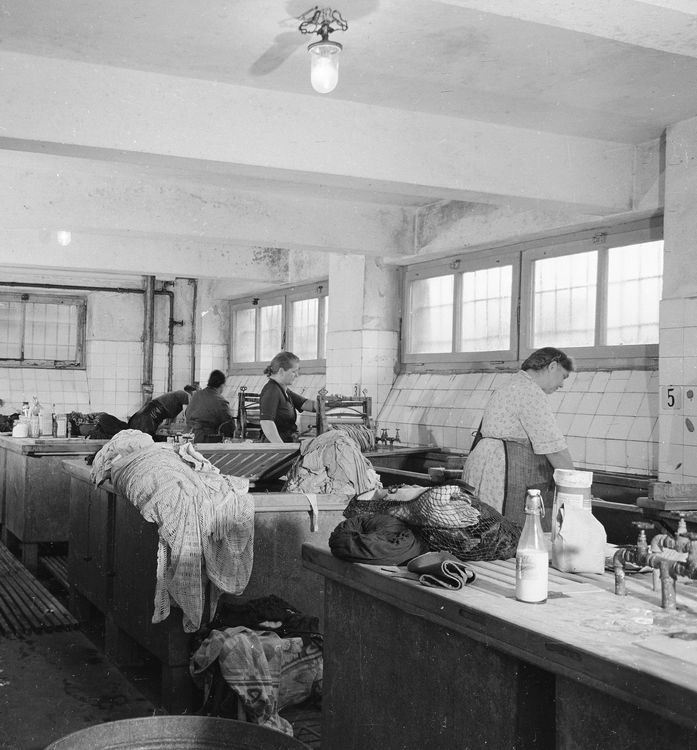

Fruit and vegetable cooperative, Poland, 1937 (Source: NAC)

Yet apart from improving the living conditions of lower-class women and their families, co-operatives also provided women with a space for labour activism separate from political parties and trade unions. Activists sought to make women – all women, regardless of whether they were involved in paid labour or not – more aware of their economic, social, and political power. Co-operative organizations gave their participants opportunities to learn grassroots organizing, sharpen their knowledge about society and economy, and eventually become activists in their own right. Co-operative work helped key activists expose the connections between paid and unpaid work, between the workplace and the household, and valorize women’s unpaid reproductive labour. Activist authors such as Emmy Freundlich from Austria and Marie Nečásková from Czechoslovakia relentlessly stressed the potential of co-operatives as drivers of societal transformation, pointing out that they offered a way to organize the economy in a fairer, more egalitarian way.

Bolstering women’s power as consumers and building networks of women activists were among such overarching goals that could lead to lasting change. These networks of activists were emerging not only locally: The International Co-operative Women’s Guild (ICWG), established in 1921, built on and framed these grassroots efforts.

Power of consumers

Women involved in consumer co-operatives focused on the consumer power of the “women with the basket”. In a pamphlet published in 1931, the Central Union of Czechoslovak Co-operatives underlined that “housewife shoppers” were a force to be reckoned with on the market, as millions of Czechoslovak crowns went through their hands every year. When organized collectively, these consumption choices also encouraged the development of producer co-operatives. Promoting the goods produced by such co-operatives and encouraging women to buy them was an important focus of activists from consumer co-operatives. In turn, this increased reliance on the goods offered by consumer co-operatives helped the organizations develop further, expanding their capacity and eventually significantly improving the purchasing power of individual households. Taken together, these efforts could have far-reaching results and restructure the economy, bringing about a distributive system based on the concern for collective well-being rather than profit-seeking.

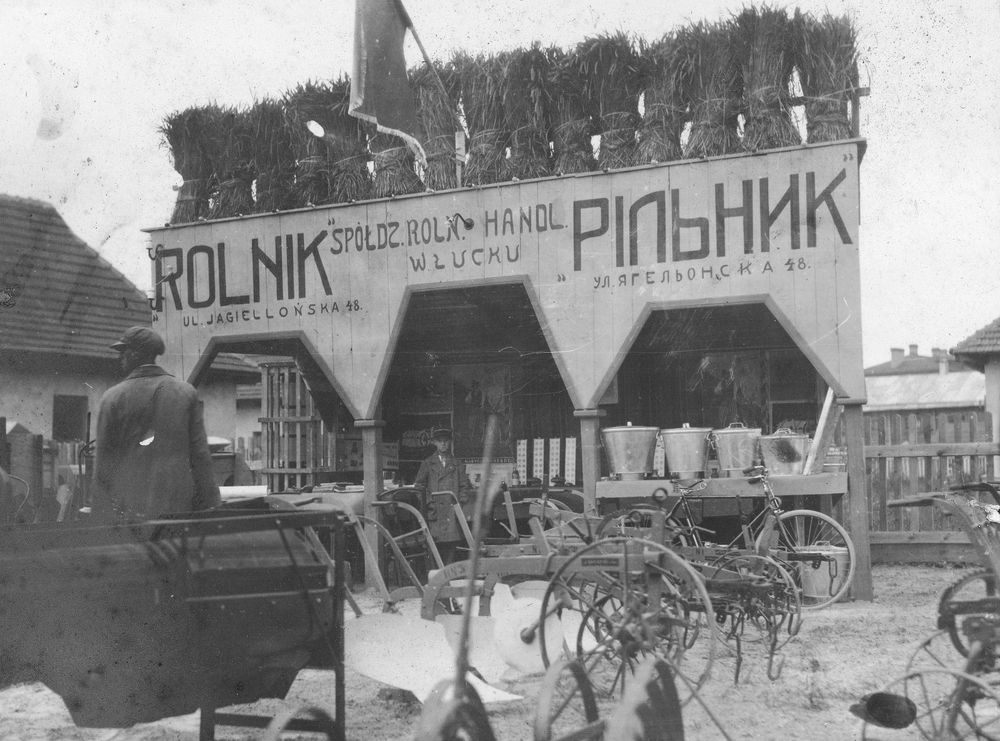

Cooperative store at an agricultural exhibition in Lutsk (then Poland, today Ukraine), 1928 (Source: NAC)

Building activist networks

The ICWG was the leading international organization that connected national women’s co-operative organizations. The Austrian Co-operative Guild was among its founding members in 1921, and the Czech-language organization from Czechoslovakia joined in 1927. In the following years, more organizations from Central and Eastern Europe became members of the ICWG.

Emmy Freundlich, the long-term president of the ICWG, was perhaps the main driver behind efforts to build up international collaboration between local co-operative organizations. A prominent activist in the social democratic movement in her native Austria, Freundlich travelled extensively, tirelessly working to establish contacts and promote the ICWG. Her works on the role of women in the co-operative movement and women’s household labour were translated in local languages, including Bulgarian and Czech.

The ICWG organized trainings, distributed key publications about the mission and potential of cooperatives, spread knowledge about best practices for organization, facilitated transnational collaboration, and provided a platform for discussions. The relationship was fruitful in the other direction too: the ICWG could rely on national branches as sources of new ideas, activist practices, and political capital. Together with its local branches and its work building connections with women’s organizations, the ICWG aimed to change women’s position in the co-operative movement by educating women and promoting their participation in the co-operative movement in rank-and-file and leadership positions alike.

While many co-operative activists did not challenge or even question the gendered division of labour that meant unpaid household labour was overwhelmingly performed by women, their efforts aimed at radically changing the position of women’s labour within the society. Making this unpaid work more visible – and more valued – was part of their activist agenda. As such, their work not only had the immediately tangible result of making, for example, higher-quality consumer goods more affordable for working-class families but also aimed at empowering women as labourers and consumers.