Women Labour Activists Internationally

Fully appreciating the role of women from Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe in labour activism at the international level is an ongoing challenge. Despite their participation in trade unions, socialist movements, and various other strands of labour activism, women from these regions had to overcome significant challenges to reach the international level of activism. Material scarcity, linguistic barriers, and political divides, particularly during the Cold War, were among such hurdles. These obstacles also meant that many women activists participated in more subtle – and less costly – ways: for instance, through correspondence rather than attending major international conferences. All of this contributed to the limited perception of their work, thus making the reconstruction of their participation an important yet laborious task.

Different ways of being international

Numerous stories show that women from different organizations, institutions, and associations found their way onto the international scene. In the first half of the twentieth century, co-operative activists maintained close ties that crossed state borders and built the International Co-operative Women’s Guild to coordinate and promote their efforts. When it came to international organizations established in the wake of World War I, such as the International Labour Organization, women from Central and Eastern Europe also managed to increasingly reinforce their presence. Women trade unionists from across the region became permanent fixtures in the workings of international trade union organizations already in the interwar period. After World War II too, and notwithstanding the Cold War divides, women labour activists shaped key debates, for instance on equal pay and the protection of working mothers. Women communist, social democratic and Catholic activists participated in formal international movements and cultivated their own informal cross-border networks that supported and increased the visibility of more disadvantaged activists. Communist activists facing persecution in their native countries, such as Zehra Kosova and Suzana Pârvulescu, found temporary refuge in the Soviet Union. There, they received activist and vocational training and built stronger militant connections. For a considerable number of women, like Ecaterina Arbore, such exile ended in their tragic death in the Soviet Great Terror.

Women activists in the region worked in rapidly shifting political conditions, from the collapse of empires to the rise of state socialist regimes and beyond. The connections the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian Empires had fostered were part of their heritage. Activists often shared belongings that were not defined exclusively by the nation-states that emerged after World War I but reflected a common imperial experience. The enduring importance of the Austrian left-wing movement for many activists across the region, including Polish and Romanian ones, is a notable regional specificity.

French, German, Belgian, Polish, Czech, British, and Italian delegates to the First International Congress of Working Women, 1919, Washington, D.C. (Source: Library of Congress)

The local and the international

Crucially, the local and international levels of activism were not disconnected. Instead, activists simultaneously organised, distributed information, exchanged experiences, shared and adapted activist practices, and raised awareness of new issues in local and international arenas. These circulations shaped what happened locally but also what was being discussed and done internationally.

There were also many tensions between these levels. Some women activists – especially those who had direct experience of the industrial workplace – preferred to focus on grassroots organising, believing that international politics were too moderate or disconnected from the lived reality of women workers. For local governments, committing to international labour standards was not a seamless process. For example, while the ILO provided benchmarks in areas such as vocational training and equal pay, these commitments often proved difficult and costly to implement in national contexts. Cultural and economic factors, such as traditional gender roles and systemic discrimination, posed additional challenges to the realization of these policies. Yet even when international cooperation was sporadic and unsystematic or even halted by repressive politics at the national level, it still was extremely meaningful for the activists. For trade union women activists in Turkey in the 1960s and 1970s, for example, learning about the struggles of women elsewhere helped them voice their own demands and concerns.

Correspondence Committee for Women’s Work

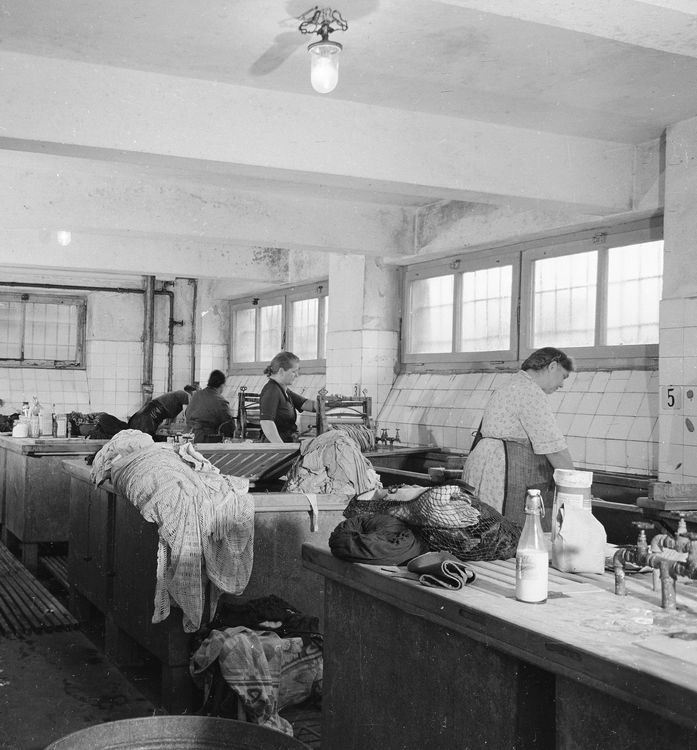

There are many examples of women seeking to mobilise to overcome the marginalisation they faced on the international scene, the 1919 International Congress of Working Women being a prominent one. Increasingly, however, international organizations also tried to include women, albeit initially in a limited way. The Correspondence Committee for Women’s Work, inaugurated in 1932, illustrates how the ILO included activists and experts on women’s labour in its workings. Through the Correspondence Committee, ILO officials could tap into the wealth of knowledge about women workers across Europe. They solicited reports from experts who spoke local languages and were extremely familiar with the issues: trade unionists like Anna Boschek or Grete Daurer (married Rehor), co-operative activists like Emmy Freundlich, (former) labour inspectors like Halina Krahelska, but also occupational physicians, activists from the women’s movement, and state officials. This committee did not meet in person until 1946 – unsurprisingly, no members from Central and Eastern Europe could be present. Nonetheless, the Committee’s work drew attention to the problems of women’s labour and women from Central and Eastern Europe made available to the ILO information about the conditions of women workers “on the ground”.

International participation after World War II

In a world preoccupied with post-war reconstruction women labour activists gradually strengthened their position in the international sphere. The Correspondence Committee continued its work until it was replaced by the Panel of Consultants on the Problems of Women Workers in 1959. In international trade union organizations, women remained a minority, but some of them now managed to attain leadership positions: In 1956, Elena Teodorescu from Romania, for example, became the first woman to be elected to the leading position in the Secretariat of the World Federation of Trade Unions. In this capacity, she was part of WFTU delegations that repeatedly discussed the problems of working women with the ILO Director-General.

Opening of the World Congress for International Women's Year in East Berlin in 1975 (Photographer: Heinz Junge, source: Bundesarchiv Bilddatenbank, Bild 183-P1020-418]

During the Cold War, the competition between socialist and capitalist regimes also meant that they sought to expand their spheres of influence. Labour organizations from across the political spectrum sought to attract new activists. At a conference on problems of women workers organised by the International Federation of Christian Trade Unions (IFCTU) in Elewijt (Belgium) in 1967, delegates came from a large number of African, Latin American, and Asian countries. Grete Rehor, by then the minister of social affairs in her native Austria, was the keynote speaker. In the 1970s, women activists from Central and Eastern Europe participated in the working meetings held by the communist-aligned WFTU in Havana (Cuba), Cotonou (Benin), Baghdad (Iraq), and on Cyprus.

Despite diverse obstacles, women’s labour activism maintained a strong transnational character. Shared experiences of gendered labour struggles fostered alliances that transcended national borders, allowing women activists to exchange ideas and strategies across regions. Even as political and economic conditions changed throughout the twentieth century, many fundamental goals of their activism – equal pay, access to education and vocational training, and better labour conditions and social provision – remained consistent. Their contributions, though frequently overlooked in dominant historical narratives, were integral to shaping international discussions on women’s work and labour rights.