Learning to Organize: Women’s Education in the Co-operative Movement, 1900–1940s

In the first half of the twentieth century, women in Central and Eastern Europe entered the co-operative movement not only as rank-and-file members and consumers but also as organizers and educators. Their activism was rooted in the daily realities of working-class life, where women bore the responsibility for stretching limited resources and providing for families in times of scarcity. Co-operatives became a platform through which these skills could be formalized and shared, and used for broader economic and social projects. Central to this work was education: the creation of schools, training courses, and cultural programmes that enabled women to take part in co-operatives as administrators, propagandists, and community leaders, while also reframing domestic responsibilities, and acknowledging household labour as an important part of economic life.

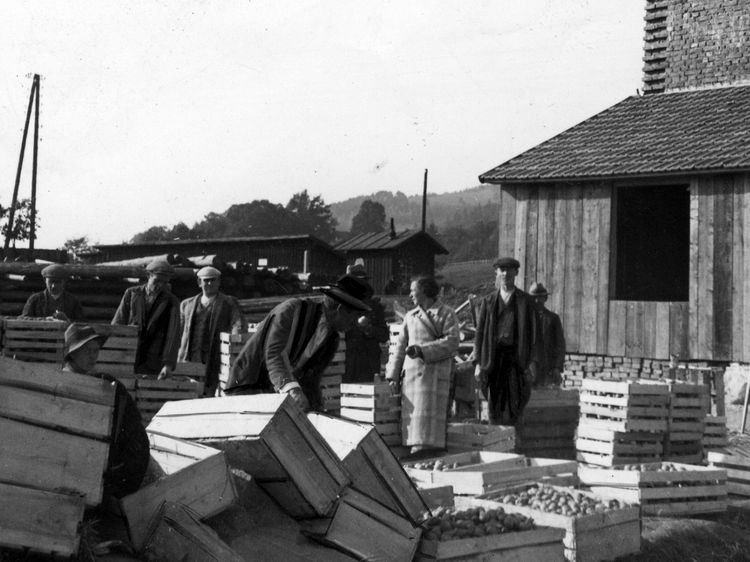

Local initiatives formed the backbone of this educational activism. In Hungary, the General Consumer Co-operative launched a training course for women warehouse clerks as early as 1916, combining six to eight weeks of practical tuition with guaranteed employment for successful candidates. In Czechoslovakia, the Association of German Economic Co-operatives opened management schools in Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary) and Teplitz (Teplice) in the 1920s and later created a boarding school for shop assistants and auditors. Women did not form the majority of students, but by 1931 they held posts across supervisory boards and committees, reflecting how training created new opportunities for them to advance in the movement. The Slovak co-operative school, in its turn, offered more than ten different courses in 1937 and counted over 160 women among its students.

Austrian guilds invested heavily in mass education. Gatherings known as “co-operative afternoons” educated women on the goals of the movement and attracted tens of thousands of women in the early 1930s, while smaller courses in Vienna and Graz trained thirty to forty selected participants in economics and trade. The intention was to make women literate in the functioning of co-operatives, so that they understood how collective purchasing could reduce prices and improve wages compared to private traders. These efforts suggest that education was understood not only as a technical tool for staffing co-operatives but also as a way of deepening women’s political and economic awareness.

Participants of a congress of the Polish League of Co-operative Women, 1937 (Source: NAC)

Educational work extended far beyond preparing administrators. In Poland, the Women’s Social Self-Help Association, founded in 1935, built an ambitious programme of lectures, reading rooms, and vocational training. Women attended classes on childcare, civic rights, and household organization, but also learnt weaving, knitting, and tailoring. Within two years, most of the fifty women trained in textile work had found employment either in Warsaw’s factories or in the association’s own workshops. Yugoslav peasant women engaged with similar forms of training through the women’s committees of the agrarian co-operative organization Economic Harmony. Here the emphasis lay on household skills, health, and gardening. These activities and skills were presented as contributions to the economic progress of peasant families and the standing of women within rural society.

Education was also a means of valuing women’s reproductive labour. Courses on hygiene, childcare, and nutrition framed domestic work as socially significant. In Bulgaria, women’s co-operatives organized summer camps and kindergartens, while in Poland co-operative washhouses mechanized laundry work, long considered one of the heaviest domestic burdens. Activists argued that by teaching women to view household responsibilities in economic terms, co-operatives could transform the family’s “shopping basket” into a tool of collective power. A Hungarian article called the housewife the “finance minister” of the family, underlining the way everyday purchases connected directly to broader economic structures.

The International Co-operative Women’s Guild circulated pamphlets and encouraged exchange between activists, and these local initiatives shaped, on the grassroots level, how women experienced and understood co-operative activism. Whether in training clerks in Budapest, organizing textile courses in Warsaw, or gathering women for lectures in Vienna, co-operatives created spaces where women could learn, teach, and redefine their roles within both the household and the wider labour movement. Education became a bridge between domestic responsibilities and public participation, allowing women to position themselves not just as caretakers of families but as active agents in reshaping economic and social life.