From House to House: Struggles of Domestic Workers in Interwar Austria

In interwar Austria, domestic workers – overwhelmingly women – faced rapidly changing labour markets and uncertain legal position in addition to the traditional challenges of the job. As Jessica Richter has shown in her research, two organizations, the Social Democratic union “Unity” and the Catholic-conservative National Association of Christian Domestic Aides, attempted to represent them and improve their situation, though neither managed to engage more than a fraction of the workforce.

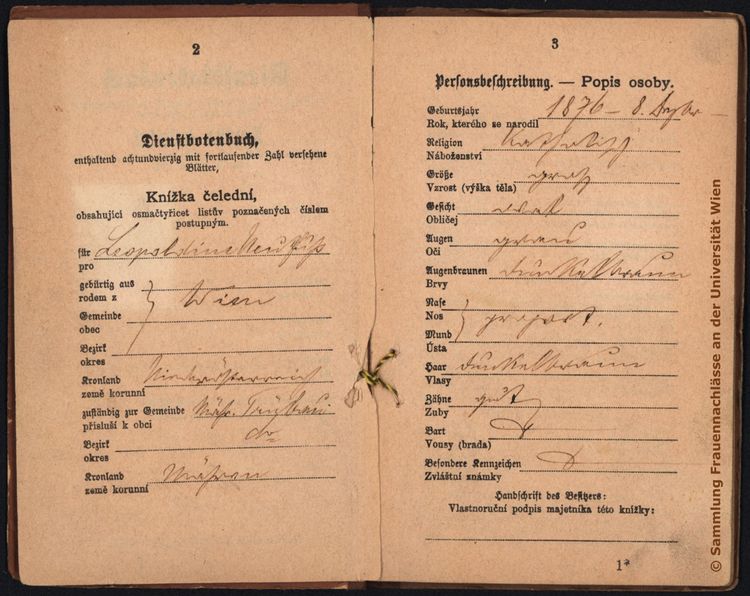

Domestic worker Martha Teichmann (1888–1977) (Source: Sammlung Frauennachlässe (Collection of Women's Personal Papers) at the University of Vienna, SFN NL 67)

Domestic service was a volatile labour market. For women, alternative opportunities for employment – as factory workers, shop assistants, or clerks – expanded from the second half of the nineteenth century. This meant fewer women were prepared to take up household posts, and during the 1880s the number of domestic servants in the Austrian lands fell by over 40 per cent. During World War I, as women filled vacancies across the economy, the number of live-in domestic workers in Vienna fell from over 100,000 in 1910 to 66,481 in 1919. This bothered the employers, and complaints of servants’ laziness, unreliability, negligence, or even theft circulated widely since the late nineteenth century. From the perspective of workers, however, moving from post to post was often the only way to leave behind unbearable conditions or conflicts within households.

Legal reform was also long overdue. Domestic workers were excluded from the full status of workers and remained dependent members of households, obliged to obey employers around the clock. The Domestic Aides’ Act of 1920 introduced contracts and limited protections, but without effective oversight these standards were rarely enforced. Even when domestic workers were included in health insurance in 1921, they were left outside of accident and unemployment insurance until the 1930s. Working hours remained excessive and precariousness grew as the number of employer households declined after the war. One worker, Hermine Kominek, born in 1907, recalled:

In Vienna, bitter years of exploitation awaited me, unemployment and hardship were great. For example, 30 girls responded to an advertisement for a maid. You can imagine that one couldn’t make any claims.

Against this backdrop, both “Unity” and the National Association of Christian Domestic Aides sought to represent domestic workers. The Christian organization, founded in 1909 with the support of the Catholic Women’s Organization, expanded across Austria, while “Unity”, founded two years later, concentrated on Vienna. Both called for legally defined rights, vocational training, and better working conditions. Yet their agendas diverged: “Unity” aimed to integrate domestic workers into the wider labour movement, treating them as a particularly exploited section of the working class. The National Association, by contrast, upheld the hierarchy between employer and employee, linking its calls for reform with expectations of loyalty and obedience.

Membership in both remained low. “Unity” reached around 4,700 members at its peak in 1928, while the National Association peaked at 5,300 in 1920 but never again matched that figure. For most domestic workers, organizations were resources to be used selectively for legal advice, job placement, or temporary shelter rather than arenas for long-term activism. The conditions of live-in employment, and the risk of dismissal for being organized, limited broader participation. For many domestic workers networks of acquaintances and extended family played a more important role in getting along as compared to organizational support provided by “Unity” and the National Association.

1 May Demonstration of the household workers (Source: Newspaper of the Social Democratic union “Unity”, "Die Hausangestellte", 1929, no. 5)

Autobiographies, diaries, and surveys expose the precarity and vulnerability of the domestic workers, but also point to strategies beyond labour organizing to improve their individual conditions. Threatening to leave sometimes gave the domestic workers leverage, as Franziska K., a maid for a wealthy elderly woman in interwar Vienna, discovered. Disgruntled with the restrictive conditions, she attempted to quit. As the sons of her employer tried to persuade her to stay, Franziska managed to wrestle out of them a few concessions, including the permission to play her folk music. Yet her victory was short-lived: a visitor of her employer harassed Franziska in her room during the night. When she tried to persuade the lady of the house to give her the room key, the employer refused. Franziska left. Although the Domestic Aides’ Act of 1920 prescribed that all domestic workers were to have a lockable room, this was not enforced.

The possibility of moving on gave workers some respite from particularly bad labour conditions: surveys from Vienna and Graz in the 1920s found that only a minority remained in the same position for more than a few months. Yet quitting the job brought its own challenges, as it meant the loss of housing, forcing workers to depend on family networks for support, whether through financial assistance, returns to parental homes, or childcare arrangements – for instance, sending children to the grandparents while mothers were looking for a new job. Experiences of these women workers reflected the contradictions of an under-regulated sector caught between private service and wage labour, where much was left to be managed in daily struggles.