On the Move: Migrant Labour Activists

Women migrants have often been overlooked in historical records, sometimes making it difficult for historians to even ascertain their presence. Well into the twentieth century, official documents have tended to focus on migrating men, often treating women, together with children, simply as unspecified “dependants”. Even when women were acknowledged separately, their economic roles were often misrepresented. For example, migrant wives who worked informally in domestic service or agriculture were frequently recorded as “housewives” rather than workers.

Despite such erasure, women continuously migrated both short distances as seasonal workers but also crossing state borders and oceans to build their lives in new countries. Their backgrounds and experiences of migration shaped their labour activism.

Group of emigrants (women and children) from Eastern Europe on deck of the SS Amsterdam, 1899 (Source: Topfoto)

Throughout the twentieth century, states have sought to control migration through various measures including border regulations, employment policies, and targeted labour migration programmes. Historically, obtaining passports and travel permits has been challenging for women across Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. In some cases, young, unmarried women required parental consent to travel while married women needed spousal permission. Moral concerns also played a role in how state officials and politicians regulating migration saw border-crossing women. To prevent sexual exploitation and human trafficking, which they saw as consequences of women being on the move, governments often restricted women’s freedom of movement as a knee-jerk reaction rather than addressing the root causes of the problem.

For women from the lower classes, migration could be a way to escape the oppressive familial structures and labour conditions at home and indeed improve life opportunities for themselves and their children. But their status as migrants could also make them more vulnerable to exploitation.

Women migrants and organized labour

Trade unions have long struggled with the question of whether and how to include migrant workers in their ranks. Making the interests of their existing members their number one priority, many unions across Central and Eastern Europe and beyond viewed migrant labour as a threat to local workers, fearing that an influx of foreign labourers would drive down wages and weaken bargaining power. This led to hostility towards migrants: for example, in 1937, the Bulgarian Tobacco Workers’ Trade Union – representing an industry employing large numbers of women – successfully pushed for legal measures against hiring foreign workers. Many unions saw migrant workers as temporary or peripheral members of the workforce and made little effort to integrate them fully into their organizations. Women migrants faced additional marginalization within the labour movement which has been dominated by men.

At the international level, the International Labour Organization (ILO) played a key role in shaping migration policies. The ILO’s 1975 Migrant Workers Convention (C143) and its accompanying recommendation (R151) are landmark instruments that address abusive conditions and the equal rights of migrant workers including the “right to geographical mobility” and the right to “preserve their national and ethnic identity” and share the advantages of social welfare policies. However, national trade unions often remained hesitant to fully embrace migrant members, as seen in Austria, where non-nationals were denied the right to run for election to work councils at their places of employment until 2002.

Despite gradual progress, throughout the twentieth century, the inclusion of migrant workers in trade unions has remained a contentious issue shaped by economic pressures, political ideologies, racism, xenophobia, and deeply ingrained biases about citizenship status and gender in the labour movement. In some cases, inclusion in existing trade unions itself became a goal of migrant women labour activists.

Challenges and contestations

Experiences of women migrants varied vastly depending on their employment sector. Domestic and hospitality service, factory work, and agricultural labour were common occupations, each bringing distinct challenges. Live-in domestic workers, for example, often faced isolation and extreme dependence on their employers. Similarly, young women who migrated from the countryside to cities were often recruited into factory jobs in which they also ended up being dependent on their employers not only for wages but also for accommodation. Fears of deportation, job loss, or lack of institutional support often discouraged women migrants from participating openly in labour protests.

Nevertheless, women migrants found ways to counteract neglect and isolation and assert their rights, often by engaging in informal or indirect activism. They used networks of solidarity, religious groups, or migrants’ associations to navigate the labour-related challenges of migration. For some, using their mobility to simply leave the exploitative employer was the last resort.

Migrant women as labour activists

Some women migrants played crucial roles in strikes, grassroots organizing, and informal resistance. In Vienna in 1893, Amalie Seidl, a young Vienna-born textile worker of Czech origin, led a strike of over 700 women against unbearable working conditions. Many of these women were rural migrants who had come to the city for work, and although they were not previously unionized, they mobilized quickly in response to poor wages, long working days, and the extreme temperatures they had to work in. In interwar Bulgaria, Mitka Grubcheva, at the time a young migrant textile worker from a poor rural family, joined the communist movement and started to rally her fellow workers against unpaid overtime as well as unsanitary living conditions and low-quality food provided by the factory. Grubcheva was fired for doing this, but the communist solidarity networks she was part of helped her find new work and new accommodations.

Poster for the European conference of Turkish woman migrants, 1985 (Source: IISG)

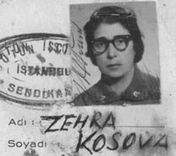

Migrant women also played key roles in labour organizing after World War II. In the 1970s, Yugoslav and Greek women workers at the Pierburg Ford plant in West Germany led strikes demanding equal pay and fair treatment. Despite facing pushback from factory management and police repression, activists resisted, turning their struggle into a widely publicized example of migrant women’s militancy. Turkish migrant women across Europe, in their turn, frustrated by the lack of inclusion in trade unions, established independent organizations such as the Federation of Turkish Women in Europe (ATKF) to advocate for their rights. Their bulletin, Woman Labourer (Emekçi Kadın), provided a platform for migrant women’s concerns and activism.These and other activisms not only improved conditions for the migrant women workers themselves, but also paved the way for future generations of migrant workers.

Women migrants have historically faced numerous barriers in their pursuit of better working conditions. At the same time, however, their contributions have often been overlooked due to marginalization based on their gender, migration status, and lower-class background. While some trade unions supported migrant struggles, many were hesitant to fully integrate such workers into their movements. These obstacles notwithstanding, migrant women found ways to improve their working and living conditions, whether through open labour conflicts, forming solidarity networks, or using mobility itself as a form of protest. Their experiences reveal the complexities of migration and labour struggles in Central and Eastern Europe, Turkey, and beyond, emphasizing the need for a more inclusive understanding of labour activism that goes beyond the histories of organized labour.