A Domestic Worker’s Life across the Empire and Beyond: A Servant’s Employment Book

Tracing the lives of migrant women can be especially challenging, even when compared to other working-class women. Mobile working women rarely moved only once, and official records of their labour trajectories are usually fragmentary at best. To reconstruct the full scope of their movements, researchers sometimes need to piece together sources from archives in different cities, countries, or even continents. Yet certain types of sources can help us reconstruct such trajectories of movement and employment: for instance, domestic servants’ employment books. In the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, these mandatory booklets contained pre-printed employment contracts and employers’ logs for each period of service. They documented dates, the nature of employment, and details about the worker’s skills and personal qualities such as loyalty, morality, and diligence.

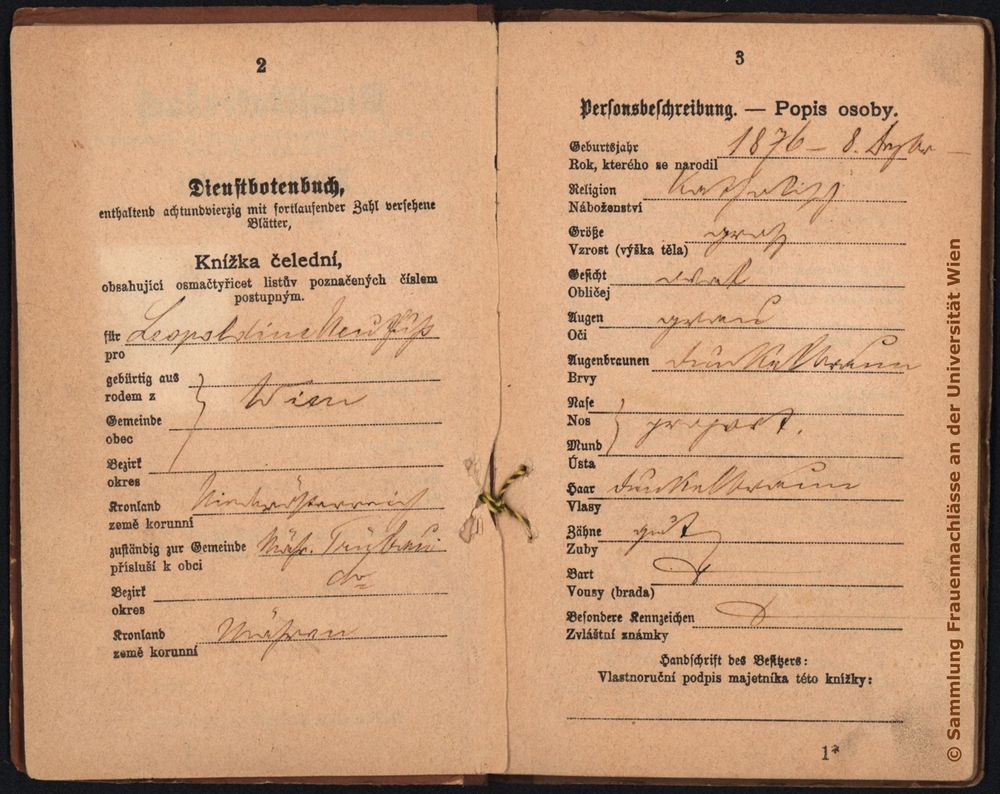

Service book of Leopoldine Neufuss (Source: Sammlung Frauennachlässe (Collection of Women's Personal Papers) at the University of Vienna, SFN NL 222 II)

Domestic service was a common form of employment for lower-class women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of the women working as live-in housemaids in larger cities across Central and Eastern Europe – from Prague to Istanbul – were migrants from the countryside. Reflecting women’s background and experiences of migration in Austria-Hungary, the service books that accompanied their professional activity could be bilingual, for example, German-Hungarian or German-Czech. Furthermore, research has shown that domestic workers often left their employers’ households due to worsening labour conditions or conflicts, adding an additional layer of mobility and making their histories even harder to follow. Although police and employers used these books as instruments of control, they are particularly valuable sources for historians as they were often the only consistent record of servants’ movements.

Service book of Leopoldine Neufuss (Source: Sammlung Frauennachlässe (Collection of Women's Personal Papers) at the University of Vienna, SFN NL 222 II)

The service book of Leopoldine Neufuß stands out in several ways. She was born in Vienna in 1876, and her citizenship status still carried ties to Moravská Třebová in Moravia (Czech lands). At the age of 14, Neufuß began working as a maid. Her service book was in German and Czech. Her first job was with the family of a master builder in in a small town in Lower Austria, and it lasted three years, while the second, in Vienna, ended after only six months.

Portrait of Leopoldine Neufuss, undated (Source: Sammlung Frauennachlässe (Collection of Women's Personal Papers) at the University of Vienna, SFN NL 222 II)

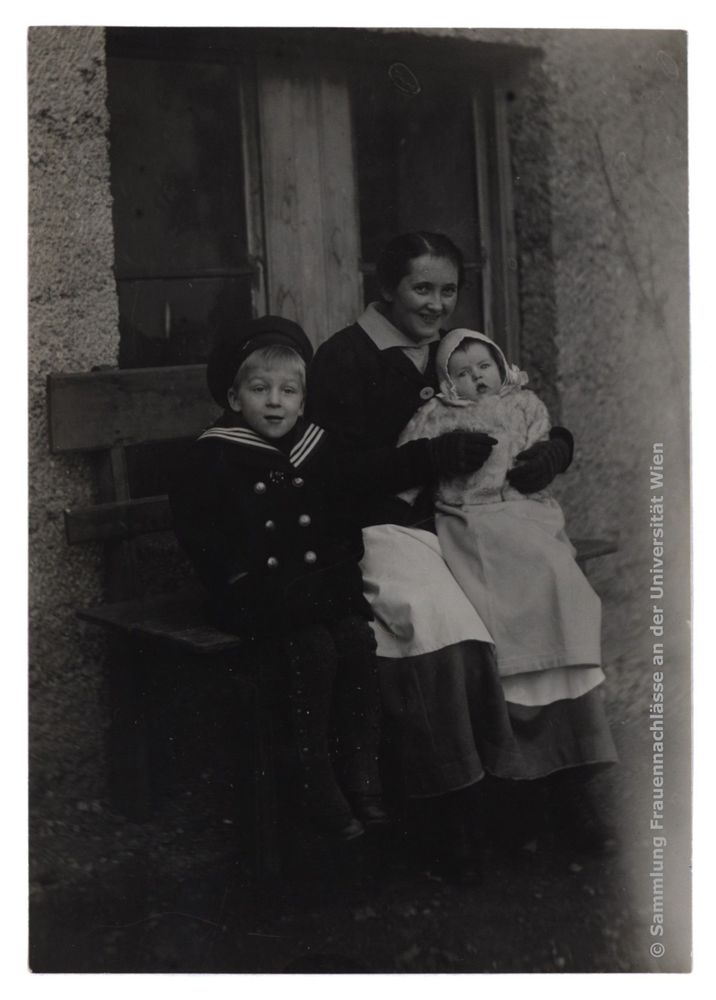

From 1894, she worked in Vienna for Mathilde and Ferdinand Lieb, the director of a Textile Industry Training Institute. She stayed with this family until 1920, then worked for their daughter, Mathilde Prey, who was married to a scientist. Neufuß remained with this family until at least 1930. She now also worked as a nanny, and they lived together in Innsbruck, Prague, and finally back in Vienna. The decades of Leopoldine Neufuß’s continuous service for two generations of the same family is somewhat unusual as domestic work was often a transitional occupation for young women.

Leopoldine Neufuss with the children she raised, ca. 1917 (Source: Sammlung Frauennachlässe (Collection of Women's Personal Papers) at the University of Vienna, SFN NL 222 II)

The survival of her papers adds to this sense of exception. Her service book and photographs are preserved in the Collection of Women’s Personal Papers (Sammlung Frauennachlässe) at the Department of History of the University of Vienna. The documents about her survived, and to this day they are conserved not in her own or her family’s archive, but among the personal papers of her employer Mathilde Prey. Such careful preservation suggests members of the household valued Neufuß’s presence and sought to remember it.

More than a record of one career, her service book points to the unevenness of the historical documentation itself. The very stability that set Leopoldine Neufuß apart made it possible for her life to be documented, while countless other women – no less central to the urban household economy – fell through the cracks of historical records.