An Enduring Demand: The Struggle for Equal Pay

The fight for equal pay, also known as the demand for “equal pay for equal work”, has been a central issue in labour movements for over a century. In a book published in 2019, experts of the International Labour Organization (ILO) called the unequal remuneration of women and men “a subtle chronic problem”. Legal advances in this regard both on the level of individual countries and internationally have been immense, so much so that equal pay today is considered a human right, yet the gender pay gap persists in practice.

What makes it so persistent? The reasons are diverse: discriminatory job evaluation systems, occupational segregation, unequal division of household and care responsibilities within the family, and long-running marginalization and sheer discrimination of women in the world of paid work. While states, trade unions, and political movements in Central and Eastern Europe have endorsed wage equality, their actual commitment to enforcing equal pay has often been inconsistent.

The persistence of the gender pay gap

One of the main reasons wage inequality has endured is the deep structural segregation of the labour market. Women have been systematically concentrated in lower-paying branches and occupations such as textiles, food production, and caregiving, while men have dominated higher-paying sectors. one of the central factors leading to such segregation. Historically, women’s limited access to vocational training and career advancement opportunities was one of the factors leading to labour market segregation and sustained wage disparities. Even in cases where trade unions endorsed equal pay in their official policies, they frequently faced employers’ opposition and failed to prioritize it in collective bargaining agreements, thereby perpetuating inequality at the practical level. In other words, activists striving for equal pay had good reasons to also call for profound changes in other domains of society: better education and vocational training for women, the fairer division of household labour, better support for working mothers, and the end of (gender-based) workplace biases and discrimination.

An example of an industry with traditional overrepresentation of women - Milk production, Zagreb, Yugoslavia, 1952 (Source: Topfoto)

Early fights for wage equality

Throughout its long history, the demand for equal pay underwent a profound evolution. Following World War I, addressing wage discrimination became part of efforts to build a more equitable postwar society and ensure social peace. The founding documents of the ILO introduced the principle that men and women should receive equal remuneration for work of equal value. In Washington, DC in 1919, the first International Labour Conference (ILC) of the ILO passed conventions limiting working hours and child labour, and establishing maternity protection. In parallel, the International Congress of Working Women brought together women labour activists who were largely excluded from the workings of the ILC. During the congress, Luisa Landová-Štychová from Czechoslovakia spoke out against protective laws aimed at women workers. According to her, in Czechoslovakia, men used laws prohibiting women from working with lead to exclude them from “the more advanced and much better-paid” jobs in the printing trades. She stressed:

It is necessary to protect the rights of women and to afford them a free choice of occupation, and to secure for them equal pay for equal work.

Throughout the interwar period, activists of the women’s and labour movements worked together to push for legal guarantees of equal pay. At the 1928 ILC, Eugenia Waśniewska, a Polish trade unionist, women’s movement activist, and politician, was a vocal advocate for minimum wage laws that built on the equal pay principle. However, many governments and trade unions were hesitant to fully commit to equal pay policies. The economic crisis of the 1930s further complicated matters, as industries sought to cut costs, sometimes replacing skilled male workers with lower-paid women. Some trade unionists, such as Anna Boschek from Austria, warned that failing to address wage disparities would incentivize employers to hire more women at lower wages, ultimately driving down wages for all workers.

Renewed efforts?

The aftermath of World War II provided a new opportunity to enshrine equal pay into legal frameworks. Following the Soviet Union, newly founded socialist states officially recognized equal pay as a fundamental labour right. The adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 reinforced the principle of wage equality, and the International Labour Organization intensified its focus on the issue. One of the most significant milestones in the struggle for equal pay was the adoption of the ILO’s Equal Remuneration Convention (C100) in 1951. The convention urged governments worldwide to establish policies promoting wage equality, leading to its ratification in multiple countries including Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Yugoslavia, and Romania. Implementation, however, continued to vary.

ILO experts on women's employment, 1956 (Source: ILO Archives)

Trade unionists and women labour activists persisted in their efforts to expose inequalities and push for stronger enforcement of equal pay policies. In 1956, the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) organized its First World Conference of Women Workers, where the principle of equal pay was at the forefront of discussions. Elena Teodorescu, an influential trade unionist, urged the International Labour Organization to take swift action to ensure governments ratified and implemented Convention C100. Over the following decades, women trade unionists became increasingly vocal about the gaps between legal commitments and workplace realities.

In state socialist regimes, where equal pay was often promoted as a core principle, the reality was also complex. Women continued to be concentrated in lower-wage industries and faced structural barriers to advancing into higher-paying positions. In the late 1960s, research conducted by the Committee of Bulgarian Women revealed that the progress made in women’s education and training did not automatically translate to better wages as women were often overqualified for the low-paid positions they held.

Different approaches

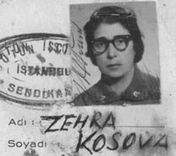

The struggle for equal pay was not only fought through legal and policy changes but also through direct worker action. Many women joined trade unions because they saw them as a vehicle for wage justice. In Turkey, Zehra Kosova was drawn to the Communist Party and its trade unions because of their commitment to wage equality and fair working hours. At times, equal pay was advanced through strikes and labour disputes rather than explicit legal mandates. In 1929, Bulgarian tobacco workers organized a strike demanding higher wages for the lowest-paid workers, a move that significantly reduced the wage gap between men and women. However, in other instances, employers answered to the push for equal pay by lowering men’s wages rather than raising women’s.

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, equal pay remained an ongoing struggle, even as international agreements continuously reinforced its importance. The 1964 International Labour Conference recognized that, despite progress, wage discrimination was still widespread, particularly in capitalist economies. The WFTU continued to push for equal pay to be prioritized in trade union agendas while national labour organizations, and women labour activists, including in socialist countries, debated the best strategies for implementation.

Despite more than a century of advocacy, the fight for equal pay remains an unfinished struggle. Legal reforms have established important frameworks for gender wage justice, but cultural norms, workplace discrimination, and structural inequalities continue to limit true economic equality. Moving forward, achieving wage justice will require not only stronger enforcement of equal pay laws but also improved access to higher-paying jobs for women, a renewed commitment from trade unions to prioritize wage equality in collective bargaining, and a sustained effort to challenge societal attitudes that have historically undervalued women’s labour.