Empowering Turkish Women? Trade Union Education

The case of women’s labour activism within the Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions (Türk-İş) during the 1960s and 1970s illustrates how international networks played a role in shaping national efforts to include women in the trade union movement. Türk-İş operated during a period of military-backed governance, but it nonetheless expanded its international connections, particularly with Western organisations like the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Labour Organization (ILO), and the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

These relationships influenced Türk-İş’s approach to worker education, a key area in which women’s issues began to be incorporated. While avoiding associations with leftist or communist ideologies was a strong motivation undergirding these programmes, they nonetheless created space for engaging with gender-specific concerns. Targeted seminars and publications addressed the position of women in the workforce and their need for education. The Türk-İş Journal began reporting regularly on women workers both in Turkey and abroad from 1963 onwards, suggesting an emerging interest in the subject.

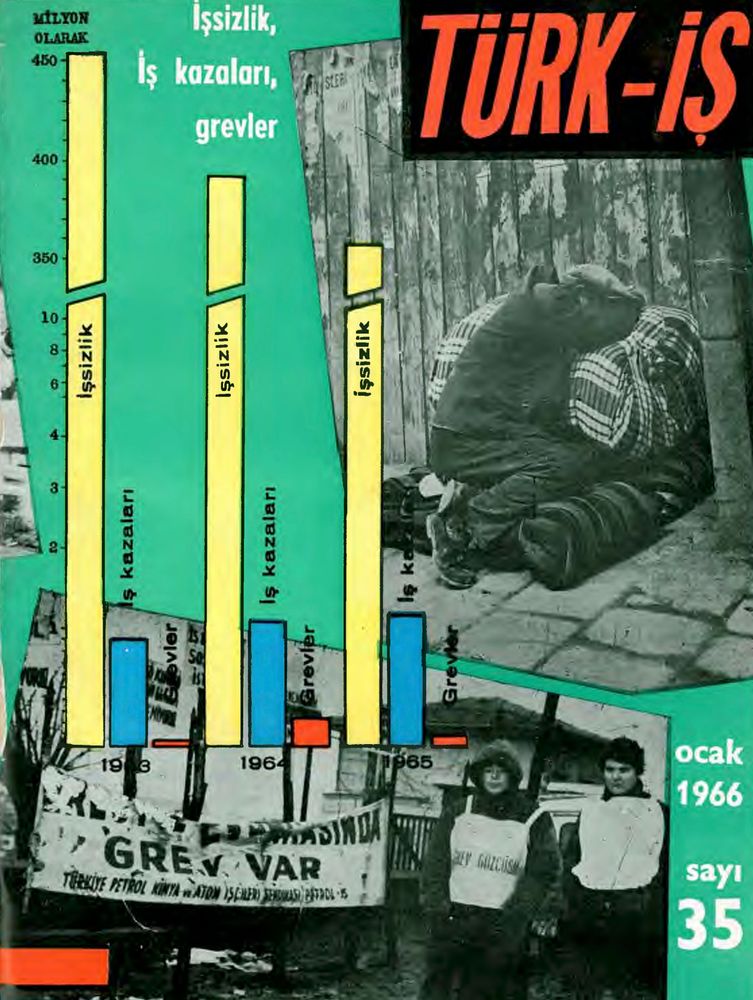

Cover of the Türk-İş Journal from 1966

A significant catalyst in these efforts was the involvement of the ICFTU’s Women’s Committee. Marcelle Dehareng from Belgium served as its secretary for almost thirty years, starting in 1957. Dehareng’s visit to Turkey in 1963, shortly after the ICFTU’s Vienna conference on women workers, marked the start of deeper cooperation between Türk-İş and the ICFTU in the area of women’s labour education. Dehareng lectured in İzmir and later met with union representatives in Ankara, promoting the idea of trade unionism among women workers. This encouraged Türk-İş to begin formal engagement with the ICFTU Women’s Committee, initially by sending a male observer in 1964, followed by incorporating women’s education into its 1965 educational strategy.

Though a dedicated women’s committee within Türk-İş was not established at this time, the groundwork was laid through activities and partnerships that centred women’s concerns. One important figure in this process was Gül Neşe Kutlu (later Erel), a research officer at Türk-İş who became an informal liaison with the ICFTU Women’s Committee. Due to her English proficiency and gender, she took on responsibilities related to communicating with the Committee and representing its initiatives to the Turkish public. Her articles in the Türk-İş Journal combined local observations with international discourse on women’s rights, reflecting both the influence of the ICFTU and the particular challenges faced by Turkish women workers, such as unequal access to vocational training and patriarchal family structures.

The collaboration between Türk-İş and the ICFTU intensified in the second half of the 1960s. Other European trade unionists, such as Elisabeth Ostermeier from West Germany, participated in seminars organised in Istanbul, expressing appreciation for the enthusiasm of the Turkish participants despite language barriers. In 1966, Gül Neşe Erel was nominated as a corresponding member of the ICFTU Women’s Committee, which facilitated more consistent communication and allowed Turkish perspectives to be included in international reports.

This momentum was not sustained. Internal conflict within Türk-İş, particularly the split that led to the creation of the leftist Confederation of Revolutionary Workers’ Unions of Turkey (DİSK) in 1967, disrupted many of its initiatives, including those focused on women. Despite receiving recognition from domestic women’s organisations, Türk-İş’s engagement with women’s issues declined. Erel’s involvement with the ICFTU waned, and by 1972, her name no longer appeared in the Women’s Committee’s correspondence list. From 1970, Türk-İş publications ceased to cover the ICFTU’s Committee’s activities altogether.

While collaboration with the ICFTU created opportunities for women’s labour education in Turkey, such efforts were constrained by broader institutional instability and the marginalisation of gender-related issues on union agendas.

Read more here